Eva Ramos Centina, wife of the author.

Eva Ramos Centina, wife of the author.

I was responsible for training my men in counterintelligence. As the war progressed and as coordination was firmly established with Australia, I gained more knowledge and experience. We learned new techniques from a small, advance team of trainers from Australia. Two years before the American liberation forces landed in the Philippines, a Filipino American officer arrived in our midst around November 1942. We came to know him only as "Tony", but his real name may have been Antonio Quesada. As to the accuracy of his full name, however, I cannot be totally sure since the mist of time has now clouded my ability to recall every detail of my war experiences. He came to Negros from Australia via submarine, and from Maricalum was sent to my unit to train us not only in using explosives to sabotage Japanese facilities, weapons systems and other assets. His tasks included coordinating with the local guerrilla movement and reassuring them at the darkest hour of the struggle that help was on its way and never to lose hope.

To boost morale, he brought printed propaganda materials, military uniforms, tents, water canteens, and American goodies like chocolates, canned goods, and cigarettes. We struck a friendship, and he told us stories about his family; he narrated how his father migrated to Florida that led him into joining the U.S. Army. His family came from Bataan, but he spoke no Tagalog. My men affectionately called him “Amboy,” a term then used to describe Filipino Americans born in the United States, back in the days when it had not yet assumed its present-day pejorative connotation. He enjoyed sleeping outdoors in a hammock.

Tony gave me a dollar bill where he wrote down his serial number, asking me and my wife to keep it as his business card. After the war, he said with confidence to stress his message that the outcome as to who would emerge victorious was never in doubt, his Army serial number would make tracking him down easy through the U.S. defense department. He also gifted me with his personal firearm, a Thompson sub-machine gun, before he left to join the American campaign in Guadalcanal. He stayed with us for only a couple of weeks, and then he was gone. The sub-machine gun was a treasured gift but I had to sell it a few years later as I did not want it around my young children in the house. The Battle of Guadalcanal, which lasted from August 1942 to February 1943, would prove to be one of the bloodiest during the war. To this day I am not sure if Tony had survived that mission. Like Cendring, he was one of the people who came into my life and left a lasting and positive impression. My regret is that I did not follow what he said. The dollar bill he gave me was either lost or spent by mistake, leaving us with no record to track down Tony.

Near the end of the war, five men appeared at my hut, which I had ordered built in my in-laws' property in Mampunay to have a semblance of family life after my wife became heavy with our first child. They came from the headquarters of Col. Salvador Abcede in the mountains bordering Negros Occidental and Oriental. They brought two jute sacks filled with cash and hurriedly left after introducing themselves and leaving the sacks with us. They said nothing else except to tell me that "you know what to do with these." My wife and I were nervous about having the money around the house, so we kept the sacks hidden in a grain silo, intending to return them to headquarters at the first opportunity. I thought it was left to us for safekeeping. When war ended, I hauled the two sacks back to headquarters and handed them to my superior officer. He took them back, but not without letting out a laugh.

"Jerry, " he said to me using my nickname, "why didn't you use the money for you and your men? Don't you know that these sacks were sent to you as your operational expenses!?" My youth and inexperience, of course, was the culprit. Had I known or even bothered to ask, I could have made better use of the money. This was a recurring topic in my family after the war, but I never regretted not having touched a single cent of the money. I have always imparted to my children that honesty is the best policy.

To boost morale, he brought printed propaganda materials, military uniforms, tents, water canteens, and American goodies like chocolates, canned goods, and cigarettes. We struck a friendship, and he told us stories about his family; he narrated how his father migrated to Florida that led him into joining the U.S. Army. His family came from Bataan, but he spoke no Tagalog. My men affectionately called him “Amboy,” a term then used to describe Filipino Americans born in the United States, back in the days when it had not yet assumed its present-day pejorative connotation. He enjoyed sleeping outdoors in a hammock.

Tony gave me a dollar bill where he wrote down his serial number, asking me and my wife to keep it as his business card. After the war, he said with confidence to stress his message that the outcome as to who would emerge victorious was never in doubt, his Army serial number would make tracking him down easy through the U.S. defense department. He also gifted me with his personal firearm, a Thompson sub-machine gun, before he left to join the American campaign in Guadalcanal. He stayed with us for only a couple of weeks, and then he was gone. The sub-machine gun was a treasured gift but I had to sell it a few years later as I did not want it around my young children in the house. The Battle of Guadalcanal, which lasted from August 1942 to February 1943, would prove to be one of the bloodiest during the war. To this day I am not sure if Tony had survived that mission. Like Cendring, he was one of the people who came into my life and left a lasting and positive impression. My regret is that I did not follow what he said. The dollar bill he gave me was either lost or spent by mistake, leaving us with no record to track down Tony.

Near the end of the war, five men appeared at my hut, which I had ordered built in my in-laws' property in Mampunay to have a semblance of family life after my wife became heavy with our first child. They came from the headquarters of Col. Salvador Abcede in the mountains bordering Negros Occidental and Oriental. They brought two jute sacks filled with cash and hurriedly left after introducing themselves and leaving the sacks with us. They said nothing else except to tell me that "you know what to do with these." My wife and I were nervous about having the money around the house, so we kept the sacks hidden in a grain silo, intending to return them to headquarters at the first opportunity. I thought it was left to us for safekeeping. When war ended, I hauled the two sacks back to headquarters and handed them to my superior officer. He took them back, but not without letting out a laugh.

"Jerry, " he said to me using my nickname, "why didn't you use the money for you and your men? Don't you know that these sacks were sent to you as your operational expenses!?" My youth and inexperience, of course, was the culprit. Had I known or even bothered to ask, I could have made better use of the money. This was a recurring topic in my family after the war, but I never regretted not having touched a single cent of the money. I have always imparted to my children that honesty is the best policy.

Photo courtesy: Wikipedia. Photo courtesy: Wikipedia.

ELUSIVE COMMISSION

The reports I filed were judged reliable and effective by my superiors so that I soon was considered for promotion from staff sergeant to second lieutenant. Some of my reports accurately pinpointed targets in the central Negros military sector, which American bombers put to good use when they conducted bombing runs to soften Japanese defenses before and after the October 1944 American landing in Leyte. Among the targets destroyed after the Leyte landing was an airfield in La Carlota, which the Japanese used to launch kamikaze attacks in Leyte. Ironically, during the early part of the war, my brother-in-law Sammy, who was detained by the Japanese during a spying operation in La Carlota, helped build that air strip through forced labor. His arrest was done not on suspicion that he was part of the resistance guerrilla movement but for being simply in town when the Japanese were in desperate need for laborers to fortify their garrison and to construct the airport. As he was just a teenage boy, the Japanese let him go when they had no more need for him. My brother-in-law and I proceeded to Camp Mambucal, a short distance from Bacolod, where there was an Army headquarters and where I expected the orders for my promotion to be signed. Early morning that day, my papers were prepared and were about to be signed by Col. Ernesto Mata in my presence when a voice intervened. It was that of Roberto S. Benedicto, son of a sugar baron, a commissioned officer who came from the law school of the University of the Philippines. “You know, Colonel,” his voiced boomed, “these fellows are my relatives but they will become dangerous officers.” (He was the first cousin of my father-in-law). Prior to our arrival, he batted for court martial proceedings to be initiated against us. His recommendation came after his father had brought to his attention a complaint filed by a civilian Japanese sympathizer who accused us of commandeering sacks of rice from his farm. It was a lie. We did ask this man for help when we requisitioned some provisions for my men. But we gave him a promissory note that entitled him to encash it when he showed up at the headquarters. But this lie was taken as gospel truth by the Benedictos, who were in a position of power and authority in that part of Negros and were duty-bound to protect civilians. Our side was never heard because the father and son tandem obviously were more concerned with appearances—of looking like impartial officials in the eyes of their constituency, unfettered even by the pull of personal relationships. The truth was the first casualty. Roberto S. Benedicto, during the presidency of Ferdinand E. Marcos, became one of the most powerful men in the Philippines. After being posted as the country’s ambassador to Japan, he returned as a successful businessman with vast holdings in banking, shipping, mass media, and full control of the sugar industry through a monopoly. It helped that he came to the financial rescue of Marcos during their law school days when the latter was accused and jailed for the murder of his father’s political opponent. Of course, we protested our innocence. I demanded that we be given a chance to face our accuser. Capt. Lorenzo Teves, who witnessed the event, turned to Colonel Mata and half-heartedly vouched for our character: “They were under me before. They were able and competent men then, but I don’t know now.” Colonel Mata (he later became a general and secretary of national defense) said nothing. We went home sorely disappointed. We must not hate our former enemies, but we must never forget Sgt. Eliodoro Ramos Jr. is shown in this list (fifth row) as having been killed in action on December 14, 1944.

Photo courtesy: USAFFE Archives |

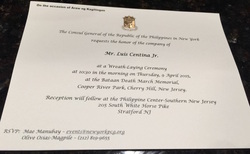

An official invitation from the Philippine Consulate General in New York to the author to attend a dedication of a war memorial on Day of Courage, a Philippine holiday honoring veterans, months prior to his death on July 18, 2015.

Photo courtesy: Centina family photo archives  General MacArthur's Leyte landing. Photo courtesy: Wikipedia. General MacArthur's Leyte landing. Photo courtesy: Wikipedia.

LIBERATION

In 1945, before the Americans entered Negros Island, my brother-in-law Ely literally dreamed about marching in the victory parade, a dream that he shared with everyone in the family. But he was an adventurer, an outgoing young man who enjoyed serenading women at night despite the uncertainty of the times. In fact, despite his duties in the underground guerrilla movement, he still managed to find time to indulge his youthful flirtations with women his age. He nearly lost his life in one such outing. Walking home at night, he was crossing Honoban Bridge when a Japanese patrol spotted him at the other end of the bridge. They ordered him to approach with his hands up in the air. But he outfoxed them by leaping into the water and swimming for his life downstream while dodging bullets raining down on him. Against my advice to stay under my command, he volunteered to be in a fighting unit to flush out remnants of the Japanese forces in San Carlos in house-to-house combat. His dream to march in the victory parade was never meant to be. He was shot by a Japanese hiding in a foxhole, and died of complications from tetanus a few days later. We learned of his death from his comrades who told us of his bravery. They buried him in an unmarked grave in that city. For a few months after liberation in 1945, my district commander, Major Reyes, assigned me as an investigator to process people accused as collaborators or war criminals. Those whose guilt was backed with strong evidence were sent to Leyte, where the War Crimes Commission tried them. I helped send six people to prison for collaboration. Some of those tried, convicted, and imprisoned were later on released with the help of high officials in government--congressmen and senators who interceded on their behalf. In 1946, after my discharge from the Army, I rejoined civilian life shunning offers to go either to Guam or Japan as part of the occupying forces there under General MacArthur. But I had no more stomach for Army life. I was just grateful that I had survived the war and was intent on raising my family. The courage and heroism of Filipino soldiers upset the timetable of the Japanese and stalled their advance towards Australia. With Australia free from enemy hands, the United States was able to regroup there and fight another day. To this day, however, the promise of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to give Filipino soldiers all the benefits that their American counterparts enjoy for fighting under the American flag remains largely unfulfilled. But the greatest tragedy does not lie in this rank injustice but in the inability of our nation to have a collective memory of the Second World War. We must not hate our former enemies, but we must never forget that our freedom is not without cost or sacrifice. General MacArthur fulfills his promise to return.

Photo courtesy: Wikipedia. |

PREVIOUS |

Page 6 |