Click to set custom HTML

General Ernesto Gidaya as a young man showed up at the hideout of the author who took him under his wings as a civilian volunteer. He later entered the Philippine Military Academy (PMA) and rose to become a Philippine Constabulary zone commander,

PMA superintendent, Philippine ambassador to Israel and administrator of the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office. Photo courtesy: vwww.pvao.mil.ph |

Ambassador Roberto S. Benedicto, a cousin of the father of the author's wife, was a ranking officer in the USAFFE. He read law at the University of the Philippines where he was a classmate of Ferdinand E. Marcos who later became president of the Philippines. A sugar baron, Benedicto was appointed president of the Philippine National Bank and later ambassador to Japan by his former classmate.

Photo courtesy: tokyope.dfa.gov.ph |

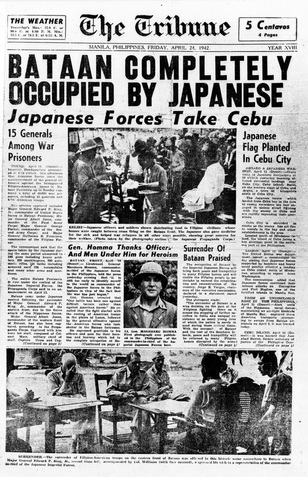

Photo courtesy: www.commandposts.com.

Photo courtesy: www.commandposts.com.

In what seemed like an eternity after the Japanese patrol had left, I climbed carefully down the coconut tree. The place was already starting to show the break of dawn. It must have been close to five o'clock in the morning. I walked cautiously at first before quickening my pace, hiding behind tall grasses growing abundantly among the coconut trees. Emerging into view as the tall grasses receded in the distance were fully irrigated rice paddies bursting with rice crop ready to be harvested. The dirt roads snaking around the rice fields were lined with tall coconut trees swaying to the cool breeze. I traversed through the rice paddies, sometimes struggling to extract my feet as they sank deeply into the soft, nutrient-filled dark mud which made growing rice possible. Hunger soon overtook me, and I acutely felt its pangs. I was weak and ready to collapse. I saw a hut and approached it to seek help. A fellow came out, disappeared back into the hut and re-emerged all dressed up and ready to go. I knew I was in a surrendered area, but I did not expect him to take me to the Japanese headquarters in the town of Pontevedra. Weak and hungry, I had no energy to fight back when he grabbed me by the neck and firmly told me that as village chief, it was his responsibility to turn me over to the Japanese garrison in the población. I nearly fainted.

At that very moment, I heard voices of friendly troops, at first faintly and then becoming louder as they drew nearer. Recognizing me, the platoon leader, 1st Lt. Teodoro Cordero, headed straight to me, with concern etched on his face upon seeing me half naked with only my pants on. His platoon was sent to the area based on intelligence information that a Japanese patrol was going to operate there the previous night but they missed each other, and no encounter occurred. After hearing my predicament, the lieutenant, who also happened to be my first cousin, ordered his men to arrest the Japanese collaborator. Another cousin of ours, Binó Centena, whose father had migrated to Negros from our hometown of Calinog years before the war, had previously discovered me at Camp Barrett by coincidence. This was before the surrender of the Philippines. It was he who revealed to me that Teodoro was also in the Army as a lieutenant and was assigned in the same military district as I was. (As I mentioned earlier, I had a falling out with my father after he had sold our rice lands without consulting with me and my two sisters by his first wife. In my anger, I changed the spelling of my last name to "Centina" from "Centena". That explains why my cousin Binó uses a different but original spelling of the family surname).

Primo (cousin) Binó and I had sought Teodoro out and had gone out with him a few times before the Japanese landing in Negros. Also from Iloilo, Teodoro came from the same town of Pototan as my mother, who was his aunt. In one of our outings, it occurred to me to recruit Primo Binó as one of my civilian operatives to give him something to do. Reporting to me at Camp Barrett was convenient for him as his family had settled in the village of La Granja where the camp was situated. It was a progressive village even during Spanish times, when it was developed to be a stock farm. Later, when the Americans came, the government conducted agricultural experiments there, focusing mostly on sugarcane production.

The Japanese collaborator was taken to guerrilla headquarters and interrogated, along with his sixteen-year old son. But before they were whisked away there, my cousin and his men stopped by the house in Mampunay to escort me home. They stayed the night along with the collaborator and his son, both of whom were tied with a rope by the bamboo staircase to my hut. My wife could not sleep that night as the teenage boy kept crying all night. A week later, word leaked out that the father was forced to flee and shot dead by the guerrillas near their camp. When I heard the shocking news, I was still at home trying to recover from my close brush with death in the hands of the Japanese. Executions without trial was not an uncommon occurrence within the guerrilla movement as the war dragged on, although I had not witnessed it personally. Of course, I did not relish the thought of people getting killed, but even knowing that this was war, I had nightmares throughout my twenties up to my late thirties.

A VOW TO HELP

After my rescue, they wasted no time in rushing me home to my worried wife (she was always in pins and needles whenever I was on a mission). Home was miles away, where I visualized my wife seeking the intercession of Our Lady of Perpetual Help as she was wont to do whenever I was on a mission. Although she was a Southern Baptist, my wife was drawn to the Virgin Mary and other Catholic practices, like praying the rosary, perhaps influenced by her classmates in middle school with whom she had developed deep friendships. The outbreak of war shattered their irenic lifestyle as well as her dream of becoming a home economics teacher. She had just finished the seventh grade when war descended upon her young life and swallowed all her dreams. It was not until 1964 when she converted to Catholicism and got baptized. She did it for our second child who wanted to become an Augustinian friar.

Along with my cousin and his men, I trudged through thickets of bushes and tall grasses to avoid detection, using an umbrella I had grabbed from the collaborator's hut to clear the way. The flimsy umbrella was no match to the unwieldy outgrowths along the way and it snapped. To replace it, I fashioned a cane out of a branch of madre de cacao, a tree abundant in the Philippines and in some Latin American countries and now becoming popular with environmentalists and farmers for its ability to prevent soil erosion. The sun shone brightly, and it was very hot and humid, making me ever more thirsty and hungry. But it did not bother me that much as I was grateful for the gift of life. I was truly convinced that God had spared me from sure death when my Japanese captor accidentally fell into the well while he was accosting me. The close shave I had with the enemy has made me and my wife very spiritual and ready to extend a helping hand to anyone who needed it. As I walked home that day, Thomas Gray's lines in his "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard," which I memorized in high school, kept popping up in my head: "The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,/ And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,/Awaits alike th' inevitable hour./ The paths of glory lead but to the grave."

It was in that same year, 1944, when the Japanese conducted an operation that the Spanish-speaking locals called juez de cuchillo. During the operation, the Japanese would swoop down on an area suspected of resistance activity and would kill everyone in sight with a bayonet. There were instances when they raped the women. Korean draftees in the Japanese Imperial Army had a special reputation for extreme brutality against civilians. But their Japanese superiors were just as guilty for allowing the cruelty in the first place. They went into the barrios, took people out of their homes, set their houses ablaze, and went on a killing spree. The night they came to our hiding place, I observed more than a dozen military trucks loaded with what looked like a company of combat troops. They kept the headlights on as they entered the village. They came from the town of La Castellana in the south.

The following day, they unloaded their weapons onto a clearing, which was only about two miles away from the headquarters of Maj. Filemon Cortez, battalion commander of a fighting unit in the area. The following night, I went with a companion to the headquarters of Major Cortez. They were tense and uneasy, fearing an imminent Japanese attack. My companion and I left right away. Through a volunteer guard, we sent a note to the company commander, warning him that an attack was very likely, based on our observation of Japanese troop movements. The next morning, Japanese bombers were seen overhead. From the air, they pounded Asay, a guerrilla stronghold, throughout the day. But there was no direct encounter between the Japanese forces and the guerrillas that day because the enemy troops went on their way to San Carlos. During the bombing run, I counted a total of twenty-eight bombs dropped by the Japanese. After the Japanese troops had left, five planes kept watch over the skies looking for any targets they had missed.

After making absolutely sure that the area was clear of any Japanese presence, I walked home that night, my body filled with lesions and boils, an effect of the incendiary bombs that exploded all around me and some of my men. When I arrived home, the house was in full panic, having heard from the civilian lookouts that the Japanese were swarming the area and looking for guerrillas. I took my wife to hide ourselves in a nearby coffee plantation, which belonged to her family. We heard gunshots up the roads that sloped down into the plantation. At the bottom of the slope was a natural trench in which we holed up ourselves, hoping the Japanese would not bother to look there.

I tightly held onto my German Luger pistol loaded with only eight rounds of ammunition, keeping it cocked just above my head. The Japanese were busy making a sweep of the area. I heard their footsteps towards our direction, their attention drawn by a barking dog. My wife was then pregnant with our first of what eventually would turn out to be seven children, not counting our stillborn child. Shivering from fear, I told my wife that we would not allow ourselves to be captured. We agreed that if capture was inevitable, I would pull the trigger on her and then turn the pistol on myself. We were prepared to die by my own hands.

We heard the Japanese approach, judging their distance to be about a mere hundred yards away. We could hear the crisp, dry leaves being crunched by footsteps. The end was near, we thought in fear. We could hear our hearts beating and our breathing getting harder as they drew closer. Then, the sound of a whistle cut through the deathly silence, and we heard hurried footsteps moving towards the opposite direction.

The whistle recalled the Japanese troops to assemble in formation and to clamber up their vehicles after a head count. The operation had ended, and it was time to return to barracks. What prompted the abrupt turnaround? It turned out that what really saved us was the cry of a three-year-old boy who was dropped to the ground by his mother seized with panic. When the Japanese commander saw the toddler, he picked up and held the child in his arms until the mother came back to retrieve her son. His encounter with the child apparently was responsible for his sudden change of heart and led him to order his men back to town.

During the remaining days of the war, I always made it a point to help people in distress if it was within my power to do so. Two of those instances happened when I was patrolling with my men. Along the way, we saw civilians suspected of being Japanese spies being made to dig up their own grave by the guerrillas. Both times, I ordered the captives freed. One was already buried neck-deep into the freshly dug hole when we happened to pass by. So grateful was he for his new lease on life that he offered me anything I wanted in his hacienda. After much prodding from him, I chose a coffee-grinding machine that my men could use to process rice and corn grains.

A NETWORK OF SPIES

Chaos ensued following the surrender of Negros. Ill-prepared, ill-trained and ill-equipped, the Philippine Commonwealth Army under the USAFFE, now reconstituted as the U.S. Armed Forces in the Philippines under the official documents of surrender signed by Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, either surrendered en masse as ordered or went underground. This was a recipe for disaster. Without a central command, some units became what the civilian population had referred to as "lost commands". They turned to banditry and committed acts of brutality against fellow Filipinos and civilians. When I joined the guerrilla movement, I was initially assigned to a fighting unit. Our first mission was to wait in ambush for a Japanese patrol operating around villages we controlled. I was given an Enfield rifle that dated back to World War I and loaded with only two bullets. Despite my serious misgivings, I positioned myself on a roadside entrenchment along with the rest of my fellow guerrillas. We waited for the enemy to come from three o'clock in the afternoon until midnight. The long wait stretched into the next day, and that was when we realized the patrol would not materialize. This was perhaps a good thing since we were not really properly equipped for the encounter.

That it was a time of extreme uncertainty is an understatement. The wait for clarity as to the command structure of the underground movement was excruciatingly painful. It was each man to his own. Roving members of the irregular Army would swoop down on villages commandeering goods and services from the civilian population and even raping the women. Some female relatives of Primo Binó became targets of these marauding bands of abusive men masquerading as guerrillas. Primo Binó expressed his fears to me about what could befall his relatives if they stayed at home with no armed protection. He had heard from neighbors that some armed men had started asking about them. Without any hesitation, I immediately dispatched a squad to fetch the young women and to bring them safely back to our hideout in Mampunay.

We monitored the movements of these "lost commands" and sent regular reports to headquarters about their illegal activities. In a 1948 military intelligence report submitted to MacArthur in Tokyo, a summary noted the presence of what the U.S. Army officially called "wild units". One such wild unit was led by a self-styled "captain" who earned his nasty reputation for menacing civilians in coastal areas around the island of Guimaras. He was unhappy about my move to take my cousin's women relatives out of harm's way. One late afternoon, he gave vent to his displeasure by showing up uninvited at my hideout. His unexpected appearance at my hut was perfectly timed while I was alone preparing supper with my wife. It soon became clear that he was there to recruit me to join his band, but not before taunting me for extending protection to the women. He knew that if he could force me to join him, he would also have the loyalty of the eighteen military men under my command as well as of my civilian operatives.

My men were all out in the field at this instance, either gathering military information or spending time with their own families in surrounding villages, in keeping with our standard practice of meeting only once every two weeks. Staying in one place together at the same time was not recommended unless we needed to assemble for an operation. The so-called captain and his three cohorts surrounded me and at gun point forcibly removed me from my hut. He taunted me for extending protection to my cousin's relatives. "So you think you're a big shot? Let's see how brave you are for poking your nose into something you have no business with," he said.

My wife's eyes never betrayed any hint of fear. Instead what I saw was her daring determination to ward off the men and make them go away. And she was barely eighteen years of age! "What do you want from my husband? He's innocent! Why are you bothering him?" she screamed at the top of her lungs. They chose to ignore her even though she was wildly flailing her arms at them. They ordered me to stand up and tied my hands behind my back. When they dragged me out of the house, my wife trailed us while sobbing loudly. The abaca rope started to hurt with the forced movements. I stumbled over the bamboo staircase but not hard enough to cause me any serious pain. It helped that the hut was elevated no more than five feet high above the ground. They pulled me towards a natural spring, our source of fresh water, which led into a road that wrapped around a hill. Over the hill was the hacienda of my father-in-law's sworn Spanish enemies. Some of their family members had been executed earlier by guerrillas whom they refused to help. Trying to reason with the goons was like talking to a brick wall. As my wife became increasingly agitated, she grew even more determined to thwart their evil designs. She kept raining curses at them as though her harsh words alone would suffice to save me from those wicked men.

As we passed the spring and headed towards the Spaniards' hacienda, I saw a group of heavily armed men headed by Primo Binó. With their firearms pointed at our direction, they ordered my abductors to drop their guns and to let me go or they would open fire. Outnumbered and outgunned, the goons immediately realize that resistance was futile. They meekly started to apologize, sounding like it was all a misunderstanding. Primo Binó was livid at their dishonesty and brazenness. He disarmed them and led his followers in beating them up until both his hands became numbed from unleashing so much punishment. Our civilian lookouts had noticed the commotion at my hut and had run for help. Their vigilance saved me from being forced to become a part of the wild unit of the so-called captain. We would later learn about the rogue leader's gruesome fate from other guerrillas at the end of the war. From Negros, he brought his terror show to Mindanao where he would meet his end. One of his victims there was a Muslim whose death was avenged by fellow Muslim warriors. They captured the wrongdoer, attached a block of cement around his feet and boarded him in a kumpit, where he was thrown overboard into the open sea. The kumpit was a dreaded symbol of terror along coastal communities in the Visayas because Muslim pirates during the pre-war era used this swift vessel to abduct young Christian maidens whom they forced into marriage.

My assignment with the G-2, 7th Military District, Negros Island Force, called for me to establish a spy network across the Central Negros Sector. This meant the authority to recruit informers and civilian collaborators whose mission was counterintelligence. We reported directly to the district intelligence commander, Maj. Rodolfo Reyes. I was able to assemble over a dozen civilian operatives in addition to the eighteen enlisted men already under my command to help me in the operations. I chose competent men and women who were ready to serve their country in her time of need without thinking of the dangers it entailed. They all proved to be brave and loyal, two character traits that I looked for in every recruit.

One of my wife’s younger brothers, Sammy, was one such brave soul. Only in his teens at that time, he would volunteer to go into town, smuggling in coded messages. Our informants would send back important information on Japanese troops and materiel, which Sammy brought back to our hideout hidden in gourds. Another volunteer was a lanky teenage boy, who must have been a year shy of his eighteenth birthday when he came to my hideout one night trying to escape execution by the guerrillas who suspected him of being a collaborator. Anyone who chose to stay in town centers in compliance with the Japanese surrender instructions immediately fell under a cloud of suspicion.

The teenager that I took under my wings was Ernesto Gidaya, who became one of my orderlies, taking care of household chores. After the war, he entered the Philippine Military Academy and went on to serve his country with honor and distinction. He became a brigadier general and commander of the Third Philippine Constabulary Zone, superintendent of the Philippine Military Academy, and ambassador of the Philippines to Israel.

While administrator of the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office, his critics questioned his appointment, casting doubt on his qualifications as a World War ll veteran. His critics, of course, were blinded by their own selfish political agenda, barking up the wrong tree. The late General Gidaya was a real war hero, risking his life as a young man in the service of his nation. As his military superior during the war, I executed an affidavit vouching for his World War II service under my command as well as for his character. He turned to me for help to counter the propaganda being dished out by politicians who wanted him replaced with their own candidate. Under my direction, he gathered intelligence information that I collated and sent to MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia, valuable information used by American bombers in targeting Japanese military positions in Central Negros prior to and during the liberation of the province.

I met with my men once every two weeks, avoiding staying in the same place to prevent suspicion. We did not directly engage the enemy; instead, we spied on their movements, counted their personnel strength and weapons capability, and reported these to higher headquarters. It meant being away from my wife for up to two weeks at a time as I hiked at times by myself or with an aide to guerrilla headquarters, which was located in southwest Negros island, in the vast mountain fastnesses of Maricalum in Sipalay town. On the map of Negros island, which looks like a boot, Sipalay sits on the ankle of the boot. We had to battle hunger, thirst, wild jungle animals, poisonous snakes and giant spiders and other insects—even wild plants—to get there. There was always the danger of contracting malaria from the swarm of mosquitoes which would feast on us as we tried to get some sleep at night. Many times, I suffered from dehydration and diarrhea. The tropical heat was unbearable and stifling in some portions of the trek, especially from noon to late afternoon. But once we reached the thick canopy of the jungle, it shielded us from the unforgiving sun and ushered us into another sort of peril as it turned day into night. In the mountain jungles, the weather was unpredictable. It often rained and it was always cold at night.

In one such hikes to reach Maricalum, I came upon a settlement of Bukidnons (highlanders), a minority group living in the hinterlands and considered as among the first inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago. Waves of migration during the early history of the islands had uprooted them from their ancestral homes in the lowlands. They were scarcely untouched by civilization due to their almost inaccessible location. Before the war, some of them would occasionally venture into town to barter some wild fowls with clothes or cooking utensils. They engaged in low-scale mining activities, mostly for decorations and accessories. Soaked in sweat from the heat and from the rain, I had contracted high fever and needed help. While almost in a state of delirium, I was given the best spot to sleep in a hut. They cooked some food for me but I had no stomach for it after seeing how it was prepared. From my bedside, I espied them producing coconut milk by masticating coconut flesh and spitting it out into a boiling stew of vegetables and wild boar. Politely turning down their offer to eat their delicacy without offending them was easy since I was ill. The hospitality of these simple mountain folk was remarkable. An herbolario prescribed for me a fresh herbal concoction which he mixed in a mortar and pestle. After a few days, my fever was gone and I regained my strength to feel well enough to continue with my journey.

I must mention that throughout the war, although we felt the pangs of hunger, my wife and I did not have much appetite for even our favorite dishes. We were always on the edge. While hopeful that the Allies would eventually triumph and convinced that we were on the right side of history, there was always doubt as to the outcome of the war. Very little information from Australia, where MacArthur was headquartered, trickled in. Foolishly, at the darkest point of the war, the guerrilla leaders of my military sector tried to send missions to Mindanao to establish contact with the resistance movement there, whom they thought knew the game plan of the Allies to liberate the Philippines. Among those tapped to carry out this risky mission included me and a number of my men. Luckily, after several attempts of setting out toward Mindanao in a small sailboat had failed, the plan was altogether abandoned. It was only in late 1942 when we started receiving updates from headquarters about the movements of the Allies in the Pacific.

It was part of the tasks of G2 (military intelligence) to track down and arrest abusive soldiers. We ensured that they were brought before the bar of justice and court martialed for their offenses. Because of this aspect of our job, we commanded the respect of fighting units, sometimes composed of soldiers who misused their superiority by virtue of arms over hapless civilians. There was no effective civilian authority underground, and control of the guerrilla movement was exercised through military justice, and we were its eyes and ears.

At that very moment, I heard voices of friendly troops, at first faintly and then becoming louder as they drew nearer. Recognizing me, the platoon leader, 1st Lt. Teodoro Cordero, headed straight to me, with concern etched on his face upon seeing me half naked with only my pants on. His platoon was sent to the area based on intelligence information that a Japanese patrol was going to operate there the previous night but they missed each other, and no encounter occurred. After hearing my predicament, the lieutenant, who also happened to be my first cousin, ordered his men to arrest the Japanese collaborator. Another cousin of ours, Binó Centena, whose father had migrated to Negros from our hometown of Calinog years before the war, had previously discovered me at Camp Barrett by coincidence. This was before the surrender of the Philippines. It was he who revealed to me that Teodoro was also in the Army as a lieutenant and was assigned in the same military district as I was. (As I mentioned earlier, I had a falling out with my father after he had sold our rice lands without consulting with me and my two sisters by his first wife. In my anger, I changed the spelling of my last name to "Centina" from "Centena". That explains why my cousin Binó uses a different but original spelling of the family surname).

Primo (cousin) Binó and I had sought Teodoro out and had gone out with him a few times before the Japanese landing in Negros. Also from Iloilo, Teodoro came from the same town of Pototan as my mother, who was his aunt. In one of our outings, it occurred to me to recruit Primo Binó as one of my civilian operatives to give him something to do. Reporting to me at Camp Barrett was convenient for him as his family had settled in the village of La Granja where the camp was situated. It was a progressive village even during Spanish times, when it was developed to be a stock farm. Later, when the Americans came, the government conducted agricultural experiments there, focusing mostly on sugarcane production.

The Japanese collaborator was taken to guerrilla headquarters and interrogated, along with his sixteen-year old son. But before they were whisked away there, my cousin and his men stopped by the house in Mampunay to escort me home. They stayed the night along with the collaborator and his son, both of whom were tied with a rope by the bamboo staircase to my hut. My wife could not sleep that night as the teenage boy kept crying all night. A week later, word leaked out that the father was forced to flee and shot dead by the guerrillas near their camp. When I heard the shocking news, I was still at home trying to recover from my close brush with death in the hands of the Japanese. Executions without trial was not an uncommon occurrence within the guerrilla movement as the war dragged on, although I had not witnessed it personally. Of course, I did not relish the thought of people getting killed, but even knowing that this was war, I had nightmares throughout my twenties up to my late thirties.

A VOW TO HELP

After my rescue, they wasted no time in rushing me home to my worried wife (she was always in pins and needles whenever I was on a mission). Home was miles away, where I visualized my wife seeking the intercession of Our Lady of Perpetual Help as she was wont to do whenever I was on a mission. Although she was a Southern Baptist, my wife was drawn to the Virgin Mary and other Catholic practices, like praying the rosary, perhaps influenced by her classmates in middle school with whom she had developed deep friendships. The outbreak of war shattered their irenic lifestyle as well as her dream of becoming a home economics teacher. She had just finished the seventh grade when war descended upon her young life and swallowed all her dreams. It was not until 1964 when she converted to Catholicism and got baptized. She did it for our second child who wanted to become an Augustinian friar.

Along with my cousin and his men, I trudged through thickets of bushes and tall grasses to avoid detection, using an umbrella I had grabbed from the collaborator's hut to clear the way. The flimsy umbrella was no match to the unwieldy outgrowths along the way and it snapped. To replace it, I fashioned a cane out of a branch of madre de cacao, a tree abundant in the Philippines and in some Latin American countries and now becoming popular with environmentalists and farmers for its ability to prevent soil erosion. The sun shone brightly, and it was very hot and humid, making me ever more thirsty and hungry. But it did not bother me that much as I was grateful for the gift of life. I was truly convinced that God had spared me from sure death when my Japanese captor accidentally fell into the well while he was accosting me. The close shave I had with the enemy has made me and my wife very spiritual and ready to extend a helping hand to anyone who needed it. As I walked home that day, Thomas Gray's lines in his "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard," which I memorized in high school, kept popping up in my head: "The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,/ And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,/Awaits alike th' inevitable hour./ The paths of glory lead but to the grave."

It was in that same year, 1944, when the Japanese conducted an operation that the Spanish-speaking locals called juez de cuchillo. During the operation, the Japanese would swoop down on an area suspected of resistance activity and would kill everyone in sight with a bayonet. There were instances when they raped the women. Korean draftees in the Japanese Imperial Army had a special reputation for extreme brutality against civilians. But their Japanese superiors were just as guilty for allowing the cruelty in the first place. They went into the barrios, took people out of their homes, set their houses ablaze, and went on a killing spree. The night they came to our hiding place, I observed more than a dozen military trucks loaded with what looked like a company of combat troops. They kept the headlights on as they entered the village. They came from the town of La Castellana in the south.

The following day, they unloaded their weapons onto a clearing, which was only about two miles away from the headquarters of Maj. Filemon Cortez, battalion commander of a fighting unit in the area. The following night, I went with a companion to the headquarters of Major Cortez. They were tense and uneasy, fearing an imminent Japanese attack. My companion and I left right away. Through a volunteer guard, we sent a note to the company commander, warning him that an attack was very likely, based on our observation of Japanese troop movements. The next morning, Japanese bombers were seen overhead. From the air, they pounded Asay, a guerrilla stronghold, throughout the day. But there was no direct encounter between the Japanese forces and the guerrillas that day because the enemy troops went on their way to San Carlos. During the bombing run, I counted a total of twenty-eight bombs dropped by the Japanese. After the Japanese troops had left, five planes kept watch over the skies looking for any targets they had missed.

After making absolutely sure that the area was clear of any Japanese presence, I walked home that night, my body filled with lesions and boils, an effect of the incendiary bombs that exploded all around me and some of my men. When I arrived home, the house was in full panic, having heard from the civilian lookouts that the Japanese were swarming the area and looking for guerrillas. I took my wife to hide ourselves in a nearby coffee plantation, which belonged to her family. We heard gunshots up the roads that sloped down into the plantation. At the bottom of the slope was a natural trench in which we holed up ourselves, hoping the Japanese would not bother to look there.

I tightly held onto my German Luger pistol loaded with only eight rounds of ammunition, keeping it cocked just above my head. The Japanese were busy making a sweep of the area. I heard their footsteps towards our direction, their attention drawn by a barking dog. My wife was then pregnant with our first of what eventually would turn out to be seven children, not counting our stillborn child. Shivering from fear, I told my wife that we would not allow ourselves to be captured. We agreed that if capture was inevitable, I would pull the trigger on her and then turn the pistol on myself. We were prepared to die by my own hands.

We heard the Japanese approach, judging their distance to be about a mere hundred yards away. We could hear the crisp, dry leaves being crunched by footsteps. The end was near, we thought in fear. We could hear our hearts beating and our breathing getting harder as they drew closer. Then, the sound of a whistle cut through the deathly silence, and we heard hurried footsteps moving towards the opposite direction.

The whistle recalled the Japanese troops to assemble in formation and to clamber up their vehicles after a head count. The operation had ended, and it was time to return to barracks. What prompted the abrupt turnaround? It turned out that what really saved us was the cry of a three-year-old boy who was dropped to the ground by his mother seized with panic. When the Japanese commander saw the toddler, he picked up and held the child in his arms until the mother came back to retrieve her son. His encounter with the child apparently was responsible for his sudden change of heart and led him to order his men back to town.

During the remaining days of the war, I always made it a point to help people in distress if it was within my power to do so. Two of those instances happened when I was patrolling with my men. Along the way, we saw civilians suspected of being Japanese spies being made to dig up their own grave by the guerrillas. Both times, I ordered the captives freed. One was already buried neck-deep into the freshly dug hole when we happened to pass by. So grateful was he for his new lease on life that he offered me anything I wanted in his hacienda. After much prodding from him, I chose a coffee-grinding machine that my men could use to process rice and corn grains.

A NETWORK OF SPIES

Chaos ensued following the surrender of Negros. Ill-prepared, ill-trained and ill-equipped, the Philippine Commonwealth Army under the USAFFE, now reconstituted as the U.S. Armed Forces in the Philippines under the official documents of surrender signed by Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, either surrendered en masse as ordered or went underground. This was a recipe for disaster. Without a central command, some units became what the civilian population had referred to as "lost commands". They turned to banditry and committed acts of brutality against fellow Filipinos and civilians. When I joined the guerrilla movement, I was initially assigned to a fighting unit. Our first mission was to wait in ambush for a Japanese patrol operating around villages we controlled. I was given an Enfield rifle that dated back to World War I and loaded with only two bullets. Despite my serious misgivings, I positioned myself on a roadside entrenchment along with the rest of my fellow guerrillas. We waited for the enemy to come from three o'clock in the afternoon until midnight. The long wait stretched into the next day, and that was when we realized the patrol would not materialize. This was perhaps a good thing since we were not really properly equipped for the encounter.

That it was a time of extreme uncertainty is an understatement. The wait for clarity as to the command structure of the underground movement was excruciatingly painful. It was each man to his own. Roving members of the irregular Army would swoop down on villages commandeering goods and services from the civilian population and even raping the women. Some female relatives of Primo Binó became targets of these marauding bands of abusive men masquerading as guerrillas. Primo Binó expressed his fears to me about what could befall his relatives if they stayed at home with no armed protection. He had heard from neighbors that some armed men had started asking about them. Without any hesitation, I immediately dispatched a squad to fetch the young women and to bring them safely back to our hideout in Mampunay.

We monitored the movements of these "lost commands" and sent regular reports to headquarters about their illegal activities. In a 1948 military intelligence report submitted to MacArthur in Tokyo, a summary noted the presence of what the U.S. Army officially called "wild units". One such wild unit was led by a self-styled "captain" who earned his nasty reputation for menacing civilians in coastal areas around the island of Guimaras. He was unhappy about my move to take my cousin's women relatives out of harm's way. One late afternoon, he gave vent to his displeasure by showing up uninvited at my hideout. His unexpected appearance at my hut was perfectly timed while I was alone preparing supper with my wife. It soon became clear that he was there to recruit me to join his band, but not before taunting me for extending protection to the women. He knew that if he could force me to join him, he would also have the loyalty of the eighteen military men under my command as well as of my civilian operatives.

My men were all out in the field at this instance, either gathering military information or spending time with their own families in surrounding villages, in keeping with our standard practice of meeting only once every two weeks. Staying in one place together at the same time was not recommended unless we needed to assemble for an operation. The so-called captain and his three cohorts surrounded me and at gun point forcibly removed me from my hut. He taunted me for extending protection to my cousin's relatives. "So you think you're a big shot? Let's see how brave you are for poking your nose into something you have no business with," he said.

My wife's eyes never betrayed any hint of fear. Instead what I saw was her daring determination to ward off the men and make them go away. And she was barely eighteen years of age! "What do you want from my husband? He's innocent! Why are you bothering him?" she screamed at the top of her lungs. They chose to ignore her even though she was wildly flailing her arms at them. They ordered me to stand up and tied my hands behind my back. When they dragged me out of the house, my wife trailed us while sobbing loudly. The abaca rope started to hurt with the forced movements. I stumbled over the bamboo staircase but not hard enough to cause me any serious pain. It helped that the hut was elevated no more than five feet high above the ground. They pulled me towards a natural spring, our source of fresh water, which led into a road that wrapped around a hill. Over the hill was the hacienda of my father-in-law's sworn Spanish enemies. Some of their family members had been executed earlier by guerrillas whom they refused to help. Trying to reason with the goons was like talking to a brick wall. As my wife became increasingly agitated, she grew even more determined to thwart their evil designs. She kept raining curses at them as though her harsh words alone would suffice to save me from those wicked men.

As we passed the spring and headed towards the Spaniards' hacienda, I saw a group of heavily armed men headed by Primo Binó. With their firearms pointed at our direction, they ordered my abductors to drop their guns and to let me go or they would open fire. Outnumbered and outgunned, the goons immediately realize that resistance was futile. They meekly started to apologize, sounding like it was all a misunderstanding. Primo Binó was livid at their dishonesty and brazenness. He disarmed them and led his followers in beating them up until both his hands became numbed from unleashing so much punishment. Our civilian lookouts had noticed the commotion at my hut and had run for help. Their vigilance saved me from being forced to become a part of the wild unit of the so-called captain. We would later learn about the rogue leader's gruesome fate from other guerrillas at the end of the war. From Negros, he brought his terror show to Mindanao where he would meet his end. One of his victims there was a Muslim whose death was avenged by fellow Muslim warriors. They captured the wrongdoer, attached a block of cement around his feet and boarded him in a kumpit, where he was thrown overboard into the open sea. The kumpit was a dreaded symbol of terror along coastal communities in the Visayas because Muslim pirates during the pre-war era used this swift vessel to abduct young Christian maidens whom they forced into marriage.

My assignment with the G-2, 7th Military District, Negros Island Force, called for me to establish a spy network across the Central Negros Sector. This meant the authority to recruit informers and civilian collaborators whose mission was counterintelligence. We reported directly to the district intelligence commander, Maj. Rodolfo Reyes. I was able to assemble over a dozen civilian operatives in addition to the eighteen enlisted men already under my command to help me in the operations. I chose competent men and women who were ready to serve their country in her time of need without thinking of the dangers it entailed. They all proved to be brave and loyal, two character traits that I looked for in every recruit.

One of my wife’s younger brothers, Sammy, was one such brave soul. Only in his teens at that time, he would volunteer to go into town, smuggling in coded messages. Our informants would send back important information on Japanese troops and materiel, which Sammy brought back to our hideout hidden in gourds. Another volunteer was a lanky teenage boy, who must have been a year shy of his eighteenth birthday when he came to my hideout one night trying to escape execution by the guerrillas who suspected him of being a collaborator. Anyone who chose to stay in town centers in compliance with the Japanese surrender instructions immediately fell under a cloud of suspicion.

The teenager that I took under my wings was Ernesto Gidaya, who became one of my orderlies, taking care of household chores. After the war, he entered the Philippine Military Academy and went on to serve his country with honor and distinction. He became a brigadier general and commander of the Third Philippine Constabulary Zone, superintendent of the Philippine Military Academy, and ambassador of the Philippines to Israel.

While administrator of the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office, his critics questioned his appointment, casting doubt on his qualifications as a World War ll veteran. His critics, of course, were blinded by their own selfish political agenda, barking up the wrong tree. The late General Gidaya was a real war hero, risking his life as a young man in the service of his nation. As his military superior during the war, I executed an affidavit vouching for his World War II service under my command as well as for his character. He turned to me for help to counter the propaganda being dished out by politicians who wanted him replaced with their own candidate. Under my direction, he gathered intelligence information that I collated and sent to MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia, valuable information used by American bombers in targeting Japanese military positions in Central Negros prior to and during the liberation of the province.

I met with my men once every two weeks, avoiding staying in the same place to prevent suspicion. We did not directly engage the enemy; instead, we spied on their movements, counted their personnel strength and weapons capability, and reported these to higher headquarters. It meant being away from my wife for up to two weeks at a time as I hiked at times by myself or with an aide to guerrilla headquarters, which was located in southwest Negros island, in the vast mountain fastnesses of Maricalum in Sipalay town. On the map of Negros island, which looks like a boot, Sipalay sits on the ankle of the boot. We had to battle hunger, thirst, wild jungle animals, poisonous snakes and giant spiders and other insects—even wild plants—to get there. There was always the danger of contracting malaria from the swarm of mosquitoes which would feast on us as we tried to get some sleep at night. Many times, I suffered from dehydration and diarrhea. The tropical heat was unbearable and stifling in some portions of the trek, especially from noon to late afternoon. But once we reached the thick canopy of the jungle, it shielded us from the unforgiving sun and ushered us into another sort of peril as it turned day into night. In the mountain jungles, the weather was unpredictable. It often rained and it was always cold at night.

In one such hikes to reach Maricalum, I came upon a settlement of Bukidnons (highlanders), a minority group living in the hinterlands and considered as among the first inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago. Waves of migration during the early history of the islands had uprooted them from their ancestral homes in the lowlands. They were scarcely untouched by civilization due to their almost inaccessible location. Before the war, some of them would occasionally venture into town to barter some wild fowls with clothes or cooking utensils. They engaged in low-scale mining activities, mostly for decorations and accessories. Soaked in sweat from the heat and from the rain, I had contracted high fever and needed help. While almost in a state of delirium, I was given the best spot to sleep in a hut. They cooked some food for me but I had no stomach for it after seeing how it was prepared. From my bedside, I espied them producing coconut milk by masticating coconut flesh and spitting it out into a boiling stew of vegetables and wild boar. Politely turning down their offer to eat their delicacy without offending them was easy since I was ill. The hospitality of these simple mountain folk was remarkable. An herbolario prescribed for me a fresh herbal concoction which he mixed in a mortar and pestle. After a few days, my fever was gone and I regained my strength to feel well enough to continue with my journey.

I must mention that throughout the war, although we felt the pangs of hunger, my wife and I did not have much appetite for even our favorite dishes. We were always on the edge. While hopeful that the Allies would eventually triumph and convinced that we were on the right side of history, there was always doubt as to the outcome of the war. Very little information from Australia, where MacArthur was headquartered, trickled in. Foolishly, at the darkest point of the war, the guerrilla leaders of my military sector tried to send missions to Mindanao to establish contact with the resistance movement there, whom they thought knew the game plan of the Allies to liberate the Philippines. Among those tapped to carry out this risky mission included me and a number of my men. Luckily, after several attempts of setting out toward Mindanao in a small sailboat had failed, the plan was altogether abandoned. It was only in late 1942 when we started receiving updates from headquarters about the movements of the Allies in the Pacific.

It was part of the tasks of G2 (military intelligence) to track down and arrest abusive soldiers. We ensured that they were brought before the bar of justice and court martialed for their offenses. Because of this aspect of our job, we commanded the respect of fighting units, sometimes composed of soldiers who misused their superiority by virtue of arms over hapless civilians. There was no effective civilian authority underground, and control of the guerrilla movement was exercised through military justice, and we were its eyes and ears.

The author as a young man shortly after the Second World War and as a student gunning for his teacher's certificate at West Negros College (background) and fifty-nine years later (foreground). At right is the cover of Search, where this article appeared in an expanded form from the original that was first published in Philippine Digest in the early 1970s.